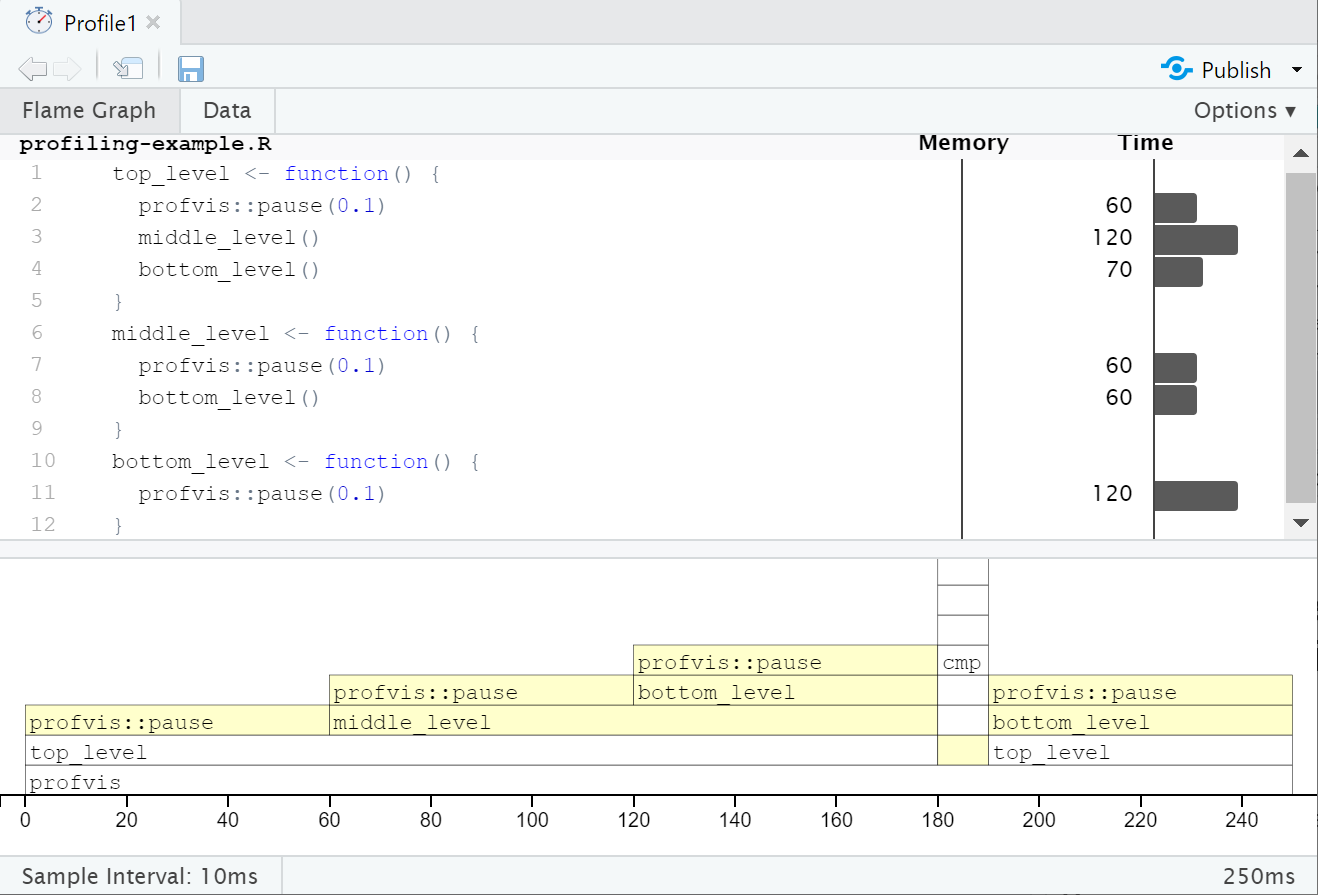

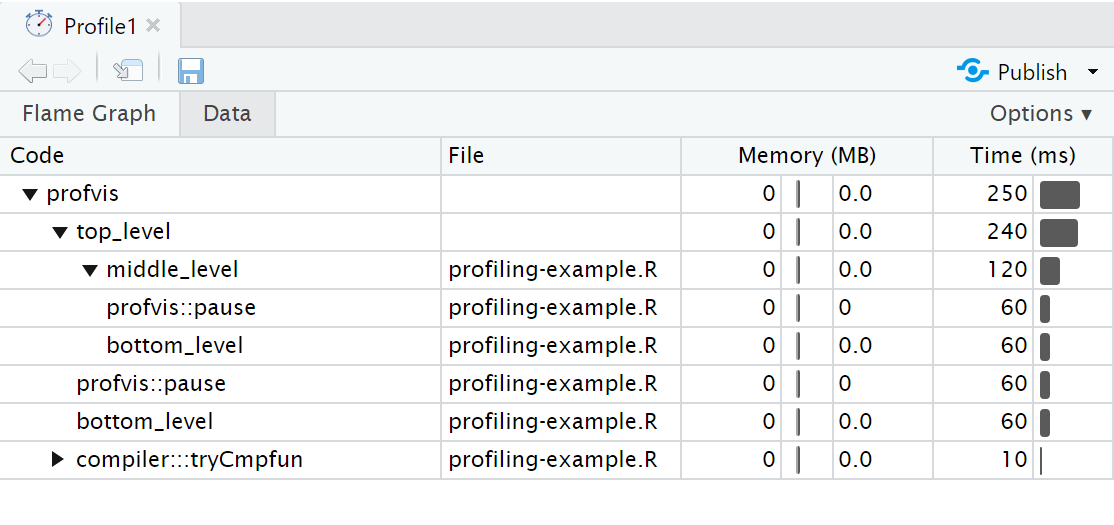

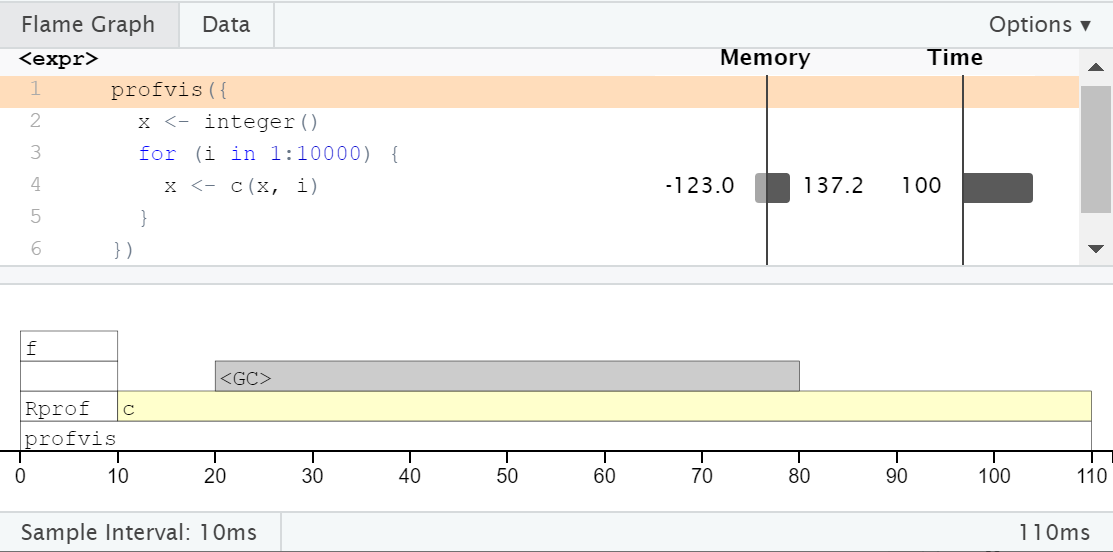

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # Bottlenecks ### <br>Dr Heather Turner<br>RSE Fellow, University of Warwick, UK<br> ### 01 April 2022 --- class: inverse middle # Profiling --- # Profiling code To make our code more efficient, we first need to identify the bottlenecks, in terms of time and/or memory usage. Profiling stops the execution of code every few milliseconds and records - The call stack: the function currently being executed, the function that it was called from and so on up to the top-level function call. - The memeory allocated and released since the last record. We will use the **profvis** package to visualise profiling results. --- # Example: nested pause functions The following code is saved in `profiling-example.R` and uses `profvis::pause` to wait 0.1s inside each function ```r top_level <- function() { profvis::pause(0.1) middle_level() bottom_level() } middle_level <- function() { profvis::pause(0.1) bottom_level() } bottom_level <- function() { profvis::pause(0.1) } ``` ??? `Sys.sleep()` can not be used as it would not show in profiling output --- # Using profvis Source the code to be profiled and pass the function call to be profiled to `profvis()` ```r library(profvis) source("profiling-example.R") profvis(top_level()) ``` An interactive HTML document will open with the results. In RStudio this will open in the source pane, click "show in new window" button to open the document in a new window. --- class: middle  --- # Interpretation The bottom plot is called a *flame graph*. The yellow bars correspond to lines in the source file shown above this graph, for which time has been recorded. In the overall time of 250ms we see - 4 equal-sized blocks for each pause of 0.1s - Nearly all time is spent in the top-level function - Nearly half the time is spent in the mid-level function - Nearly half the time is also spent in the bottom-level function as it is called twice - There is one sample where the `cmp` function is being executed (called by `compiler:::tryCmpfun`). When a function is first called, R attempts to compile it to byte code so that it can call the compiled version in subsequent calls. No changes in memory are recorded as no objects are created or deleted. --- # Data tab The Data tab shows a table with the memory and time usage for each function call. The nested calls can be expanded/collapsed to show/hide the corresponding lines.  --- # Memory profiling To illustrate memory profiling we can consider a loop that concatenates values. As it is a small code snippet, we can pass to profvis directly ```r profvis({ x <- integer() for (i in 1:10000) { x <- c(x, i) } }) ``` ---  --- # `<GC>` As expected, the majority of the time is spent within `c()`, but we also see a lot time spent in `<GC>`, the garbage collector. In the memory column next to the corresponding line in the source code, we see a bar to left labelled -123.0 and a bar to the right labelled 137.2. This means that 137 MB of memory was allocated and 123 MB of memory was released. This is because each call to `c()` causes a new copy of `x` to be created. Memory profiling can help to identify short-lived objects that might be avoided by changes to the code. --- # General principles * Avoid optimizing too soon - Get the code right first. - Write tests to validate changes to the code * Avoid over-optimization - Focus on the bottlenecks - Keep an eye on the units - will real gains be made? - Think about maintainability: readability, simplicity, dependencies * Avoid anonymous functions - Name utility functions to see them in the profile * Use microbenchmarking to assess alternative implementations --- # Monopoly .pull-left-66[In the monopoly board game, players roll two die to move round the board. Players buy assets on which they can charge rent or taxes and aim to make the most money. The squares on the board represent - Properties, train stations or utility companies to buy - Events that trigger an action, e.g. paying a tax or going to jail The *efficient* package contains the `simulate_monopoly()` function to simulate game play, which we'll use to practice profiling.] .pull-right-33[ <br> <br>  ] --- # Your Turn 1. Install the **efficient** package with the following code to keep the code source files: ```r remotes::install_github("csgillespie/efficient", INSTALL_opts = "--with-keep.source") ``` 2. Use `profvis()` to profile `simulate_monopoly(10000)`. Explore the output. Which parts of the code are slow? 3. Most of the time is spent in the underlying function `move_square()`. Use `View(move_square)` to view the source code. Make two copies of the code in separate .R files and name the functions `move_square` and `move_square2`. Edit `move_square2` to speed up the slow parts of the code. (Go to next slide for testing the updates) --- Use `bench::mark()` to test your changes. Create a wrapper for each function to run it `n` times with different seeds, e.g. ```r run_move_square <- function(n){ x <- numeric(n) for (i in 1:n) { set.seed(i) x[i] <- move_square(1) } x } ``` Then run `bench::mark(run_move_square(n), run_move_square2(n))` for suitable `n`. This ensures the new code gives the same results! When you think you have done as much improvement as you can, compare `profvis(run_move_square2(10000))` with `profvis(run_move_square(10000))`. --- class: inverse middle # Using R with C++ --- # Limits of R Sometimes you reach the limits of R: - Your code is still slow despite optimizing the computational approach and the R implementation - You could speed up the R code, but it results in very obscure, convoluted code In this case it can make sense to code parts in C++ --- # Typical scenarios There are some typical scenarios where C++ is likely to be a good idea - Loops that can't be vectorized because iterations depend on previous results - Recursive functions, or problems which involve calling functions millions of times. - Problems that require advanced data structures and algorithms that R doesn’t provide. ??? The overhead of calling a function in C++ is much lower than in R. --- # Set up to use C++ To use C++, you need a working C++ compiler. On MacOS/Windows there is some setup to do, but it will also set you up to - Develop packages in R - Install packages from GitHub that include C/C++ code On Linux, you will usually have a C++ compiler installed, but you might as well get set up to develop R packages too. --- # Linux Debian/Ubuntu ```sh apt-get update apt-get install r-base-dev ``` Fedora/RedHat: should be set up already. --- # MacOS Option 1 - [Register as an Apple developer (for free)](https://developer.apple.com/programs/register/) - In the terminal, run ```sh xcode-select --install ``` Option 2 (more convenient but installs a lot you don't need) - Install the current release of full [Xcode from the Mac App Store](https://itunes.apple.com/ca/app/xcode/id497799835?mt=12) --- # Windows Install RTools from : https://cran.r-project.org/bin/windows/Rtools/. - Select "RTools 4.0", then download and run rtools40-x86_64.exe. You will need to update RTools when you upgrade to R 4.2.0 (scheduled for release on 22 April 2022). --- # C++ basics Consider an R function `add_r()` to add two numbers ```r add_r <- function(x, y) x + y ``` Here's how we might write an equivalent `add_cpp()` function in C++ ```cpp double add_cpp(double x, double y) { double value = x + y; return value; } ``` - The type for the return value is declared first - The type of each argument must be declared - The type of intermediate objects must be declared - Return statements must use `return` --- # Rcpp To use `add_cpp()` in R we need to compile the C++ code and construct and R function that connects to the compiled C++ function. The R package **Rcpp** takes care of these steps for us. One way is to use the `cppFunction()`, e.g. ```r library(Rcpp) cppFunction(' double add_cpp(double x, double y) { double value = x + y; return value; } ') ``` --- After defining `add_cpp()` via `cppFunction()`, `add_cpp()` is available to use as a R function ```r add_cpp ``` ``` # function (x, y) # .Call(<pointer: 0x0000000071281580>, x, y) ``` ```r add_cpp(3, 5) ``` ``` # [1] 8 ``` --- # Stand-alone C++ files It is better to define functions in C++ files (extension `.cpp`). These files will be recognised by RStudio and other IDEs, with the usual benefits. The C++ file should have these lines at the top: ```cpp #include <Rcpp.h> using namespace Rcpp; ``` - The compiler will locate the Rcpp header file with functions and class definitions supplied by *Rcpp* and include the contents. - Adding the namespace means that we can use Rcpp function in the C++ code without prefxing the function names by `Rcpp::`. Above each function we want to use in R, add `// [[Rcpp::export]]` --- # Example C++ file The following is in the file `add_cpp2.cpp` ```cpp #include <Rcpp.h> using namespace Rcpp; // [[Rcpp::export]] double add_cpp2(double x, double y) { double value = x + y; return value; } ``` --- # `sourceCpp()` Now we can use `sourceCpp()` to make the C++ functions available in R ```r sourceCpp("add_cpp2.cpp") add_cpp2(5, 9) ``` ``` # [1] 14 ``` ??? could put benefits here: syntax highlighting, avoid mistakes switching from R to C code, line numbers for compilation errors, highlighting errors (e.g. missing ";") --- # C++ Basics - Every statement within `{` `}` must be terminated by a `;`. - Use `=` for assignment (`<-` is not valid). - Addition, subtraction, multiplication and division use the same operators as R (`+`, `-`, `*`, `/`). - Comparison operators are the same as R (`==`, `!=`, `>`, etc) - One-line comments start with `//`. - Multi-line comments use `/*` `*/` delimiters ```cpp /* Example multi-line comment */ ``` --- # Data types The basic C++ data types are scalars. **Rcpp** provides vector versions | R | C++ (scalar) | Rcpp (vector) | |-----------|--------------|-----------------| | numeric | double | NumericVector | | integer | int | IntegerVector | | character | char | CharacterVector | | logical | bool | LogicalVector | **Rcpp** also provides `String` as an alternative to `char` ??? Care needed with NA double: more bits used to represent a real number vs single precision - range 2^-(2^10) to 2^(2^10). vs same with 2^7 - precision ~15 d.p. vs 7 --- # Example: no inputs, scalar output ```cpp int one() { return 1; } ``` --- # Example: if/else (scalar input, scalar output) ```cpp int signC(int x) { if (x > 0) { return 1; } else if (x == 0) { return 0; } else { return -1; } } ``` --- # For loop syntax A C++ for loop has the form ```cpp for(int i = 0; i < n; ++i) { total += x[i]; } ``` - Syntax: `for(initialisation; condition; increment)` - Initialize integer `i` at zero - Continue as long as `i` is less than `n` - Increment `i` by 1 after each iteration (`++i` is equivalent to `i = i + 1`) - `total += x[i]` is equivalent to `total = total + x[i]` - **Vector indices start at zero** --- # Example: for loop (vector input, scalar output) ```cpp double sumC(NumericVector x) { int n = x.size(); double total = 0; for(int i = 0; i < n; ++i) { total += x[i]; } return total; } ``` - Use `.size()` method to find the length of a vector --- # Example: while loop (vector input, scalar output) ```cpp double sumC(NumericVector x) { int n = x.size(); double total = 0; int i = 0; while (i < n) { total += x[i]; ++i; } return total; } ``` - Use `break` to break from a while or for loop - Use `continue` to skip to the next iternation (vs `next` in R) --- # Example: vector output The following computes the Euclidean distances `$$d_i = \sqrt{(x - y_i)^2}$$` ```cpp NumericVector distC(double x, NumericVector y) { int n = y.size(); NumericVector dist(n); for(int i = 0; i < n; ++i) { dist[i] = sqrt(pow(ys[i] - x, 2.0)); } return out; } ``` `dist(n)` is used to create a numeric vector named `dist` of length `n`. `v(n)` would create a vector named `v`. --- # C++ Functions `pow` is a standard C++ functon for computing a value raised to a power. Both `pow` and `sqrt` are functions from the `<cmath>` library, see e.g. [w3schools C++ math](https://www.w3schools.com/cpp/cpp_math.asp). To use `<cmath>` functions in C++ code, we would normally need to include the `<cmath>` header in our `.cpp` file. However, **Rcpp** defines its own version of these functions, so we can use them with just the **Rcpp** header. --- # Your Turn 1. Create a new C++ file to work in. The RStudio template C++ file already includes the headers required for Rcpp. Delete the extra content, aprt from the `// [[Rcpp::export]]` comment. 2. Convert the following R function that computes a weighted mean to C++ ```r wmean_r <- function(x, w){ n <- length(x) total <- total_w <- 0 for (i in 1:n){ total <- total + x[i] * w[i] total_w <- total_w + w[i] } total/total_w } ``` 3. Use `sourceCpp()` to source in your function. Use `bench::mark()` to compare `wmean_r()`, `wmean_cpp()` and the **stats** function `weighted.mean()`. --- # Missing values in C++ data types C++ data types do not handle `NA`s in input well - `int`: use a length 1 `IntegerVector` instead - `double`: `NA`s okay (converted to `NAN`) - `char`: use `String` instead - `bool`: `NA`s converted to `true`; use `int` instead --- # Missing values in Rcpp vectors Rcpp vectors handle `NA`s in the corresponding type | Rcpp (vector) | NA | |-----------------|------------| | NumericVector | NA_REAL | | IntegerVector | NA_INTEGER | | CharacterVector | NA_STRING | | LogicalVector | NA_LOGICAL | --- # Matrices Each vector type has a corresponding matrix equivalent: `NumericMatrix`, `IntegerMatrix`, `CharacterMatrix` and `LogicalMatrix`. Create a matrix called named `m1` ```cpp NumericMatrix m1(10, 5); ``` - Subset with `()`, e.g. `m1(3, 2)` for the value in row 3, column 2. - The first element is `m1(0, 0)`. - Use `.nrow` and `.ncol` methods to get the number of rows and columns - Assign matrix elements as follows ```cpp m1(0, 0) = 1; ``` --- # Example: row sums (matrix input, vector output) ```cpp NumericVector rowSumsC(NumericMatrix x) { int nrow = x.nrow(), ncol = x.ncol(); NumericVector out(nrow); for (int i = 0; i < nrow; i++) { double total = 0; for (int j = 0; j < ncol; j++) { total += x(i, j); } out[i] = total; } return out; } ``` --- # Statistical distributions As in R, Rcpp provides d/p/q/r functions for the density, distribution function, quantile function and random generation. - Functions in the `Rcpp::` namespace return a vector. - Functions in the `R::` namespace (also provided by the **Rcpp** R package) return a scalar For example we can sample a single value from a `\(N(0, 1)\)` distribution by extracting the first element from a vector ```cpp rgamma(1, 3, 1 / (y * y + 4))[0]; ``` Or use the R::rgamma function to sample a single value directly ```Rcpp R::rgamma(3, 1 / (y * y + 4)) ``` --- # Your Turn In a new C++ file, convert the following gibbs sampler to C++ ```r gibbs_r <- function(N, thin) { mat <- matrix(nrow = N, ncol = 2) x <- y <- 0 for (i in 1:N) { for (j in 1:thin) { x <- rgamma(1, 3, y * y + 4) y <- rnorm(1, 1 / (x + 1), 1 / sqrt(2 * (x + 1))) } mat[i, ] <- c(x, y) } mat } ``` --- # Your Turn (ctd) Create a wrapper function to set the seed as follows: ```r set_seed <- function(expr){ set.seed(1) eval(expr) } ``` Benchmark your `gibbs_r()` and `gibbs_c()` functions with N = 100 and thin = 10, using your wrapper function to set the seed --- # Rcpp sugar Rcpp provides some "syntactic sugar" to allow us to write C++ code that is more like R code. One example is operating on rows or columns of matrices. So far we have seen how to update individual elements of a `NumericMatrix`. Rcpp lets us extract an update whole rows/columns, e.g. ```cpp mat(i, _) = NumericVector::create(x,y); ``` A whole column would be extracted with `mat(_, j)`. --- # Vectorized functions The vectorized random generation functions are another example of Rcpp sugar. Rcpp provide many more vectorized functions, for example: - arithmetic operators (`+`, `-`, `*`, `\`) - logical operators (`==`, `!`, `=<`) - arithmetic functions (`sqrt`, `pow`, ...) - statistical summaries (`mean`, `median`, ) In addition, Rcpp provides many R-like functions, such as `which_max` or `rowSums`, see [Unofficial API documentation](https://thecoatlessprofessor.com/programming/cpp/unofficial-rcpp-api-documentation/#sugar) for a full list. --- # Rcpp sugar: vectorized functions Recall our distance function from earlier: ```cpp NumericVector distC(double x, NumericVector y) { int n = y.size(); NumericVector out(n); for(int i = 0; i < n; ++i) { out[i] = sqrt(pow(ys[i] - x, 2.0)); } return out; } ``` with Rcpp vectorization, we can simplify this to: ```cpp NumericVector dist_sugar(double x, NumericVector y) { return sqrt(pow(x - y, 2)); } ``` --- # Example: row maximums This example combines row-indexing and a vectorized function (`max()`). ```cpp NumericVector row_max(NumericMatrix mat) { int nrow = mat.nrow(); NumericVector max(nrow); for (int i = 0; i < nrow; i++) max[i] = max( m(i,_) ); return max; } ``` --- # Your turn The following R function can be used to simulate the value of pi ```r piR <- function(N) { x <- runif(N) y <- runif(N) d <- sqrt(x^2 + y^2) return(4 * sum(d < 1.0) / N) } ``` Convert this to C++, taking advantage of the vectorized Rcpp functions. --- # References Similar scope to this module: Gillespie, C and Lovelace, R, _Efficient R programming_, _Rcpp section_, https://csgillespie.github.io/efficientR/performance.html#rcpp Going a bit further: Wickham, H, _Advanced R_ (2nd edn), _Rewriting R code in C++ chapter_, https://adv-r.hadley.nz/rcpp.html Not very polished, but broader coverage of Rcpp functionality: Tsuda, M.E., _Rcpp for everyone_, https://teuder.github.io/rcpp4everyone_en/300_Rmath.html Case studies (optimising by improving R code and/or using C++) https://robotwealth.com/optimising-the-rsims-package-for-fast-backtesting-in-r/ https://gallery.rcpp.org/articles/bayesian-time-series-changepoint/ ([Rcpp Gallery](https://gallery.rcpp.org/) has all sorts of examples, many illustrating advanced features of Rcpp). ??? Masaki Tsuda TODO Simulating pi [stat functions] Gibbs sampler example [marices] MAYBE evalCpp()